First, the claimed invention must be to one of the four statutory categories. 35 U.S.C. 101 defines the four categories of invention that Congress deemed to be the appropriate subject matter of a patent: processes, machines, manufactures and compositions of matter. The latter three categories define “things” or “products” while the first category defines “actions” (i.e., inventions that consist of a series of steps or acts to be performed). See 35 U.S.C. 100(b) (“The term ‘process’ means process, art, or method, and includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.”). See MPEP § 2106.03 for detailed information on the four categories.

Second, the claimed invention also must qualify as patent-eligible subject matter, i.e., the claim must not be directed to a judicial exception unless the claim as a whole includes additional limitations amounting to significantly more than the exception. The judicial exceptions (also called “judicially recognized exceptions” or simply “exceptions”) are subject matter that the courts have found to be outside of, or exceptions to, the four statutory categories of invention, and are limited to abstract ideas, laws of nature and natural phenomena (including products of nature). Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int'l, 573 U.S. 208, 216, 110 USPQ2d 1976, 1980 (2014) (citing Ass'n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576, 589, 106 USPQ2d 1972, 1979 (2013). See MPEP § 2106.04 for detailed information on the judicial exceptions.

Because abstract ideas, laws of nature, and natural phenomenon "are the basic tools of scientific and technological work", the Supreme Court has expressed concern that monopolizing these tools by granting patent rights may impede innovation rather than promote it. See Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 216, 110 USPQ2d at 1980; Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 71, 101 USPQ2d 1961, 1965 (2012). However, the Court has also emphasized that an invention is not considered to be ineligible for patenting simply because it involves a judicial exception. Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 217, 110 USPQ2d at 1980-81 (citing Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 187, 209 USPQ 1, 8 (1981)). See also Thales Visionix Inc. v. United States, 850 F.3d. 1343, 1349, 121 USPQ2d 1898, 1902 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (“That a mathematical equation is required to complete the claimed method and system does not doom the claims to abstraction.”). Accordingly, the Court has said that integration of an abstract idea, law of nature or natural phenomenon into a practical application may be eligible for patent protection. See, e.g., Alice, 573 U.S. at 217, 110 USPQ2d at 1981 (explaining that “in applying the §101 exception, we must distinguish between patents that claim the ‘buildin[g] block[s]’ of human ingenuity and those that integrate the building blocks into something more” (quoting Mayo, 566 U.S. at 89, 110 USPQ2d at 1971) and stating that Mayo “set forth a framework for distinguishing patents that claim laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas from those that claim patent-eligible applications of those concepts”); Mayo, 566 U.S. at 80, 84, 101 USPQ2d at 1969, 1971 (noting that the Court in Diamond v. Diehr found “the overall process patent eligible because of the way the additional steps of the process integrated the equation into the process as a whole,” but the Court in Gottschalk v. Benson “held that simply implementing a mathematical principle on a physical machine, namely a computer, was not a patentable application of that principle”); Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 611, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1010 (2010) (“Diehr explained that while an abstract idea, law of nature, or mathematical formula could not be patented, ‘an application of a law of nature or mathematical formula to a known structure or process may well be deserving of patent protection.’” (quoting Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 187, 209 USPQ 1, 8 (1981)) (emphasis in original)); Diehr, 450 U.S. at 187, 192 n.14, 209 USPQ at 10 n.14 (explaining that the process in Parker v. Flook was ineligible not because it contained a mathematical formula, but because it did not provide an application of the formula). See Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 209 USPQ 1 (1981); Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 175 USPQ 673 (1972); Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 198 USPQ 193 (1978).

The Supreme Court in Mayo laid out a framework for determining whether an applicant is seeking to patent a judicial exception itself, or a patent-eligible application of the judicial exception. See Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 217-18, 110 USPQ2d at 1981 (citing Mayo, 566 U.S. 66, 101 USPQ2d 1961). This framework, which is referred to as the Mayo test or the Alice/Mayo test, is discussed in further detail in subsection III, below. The first part of the Mayo test is to determine whether the claims are directed to an abstract idea, a law of nature or a natural phenomenon (i.e., a judicial exception). Id. If the claims are directed to a judicial exception, the second part of the Mayo test is to determine whether the claim recites additional elements that amount to significantly more than the judicial exception. Id. citing Mayo, 566 U.S. at 72-73, 101 USPQ2d at 1966). The Supreme Court has described the second part of the test as the "search for an 'inventive concept'". Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 217-18, 110 USPQ2d at 1981 (citing Mayo, 566 U.S. at 72-73, 101 USPQ2d at 1966).

The Alice/Mayo two-part test is the only test that should be used to evaluate the eligibility of claims under examination. While the machine-or-transformation test is an important clue to eligibility, it should not be used as a separate test for eligibility. Instead it should be considered as part of the "integration" determination or "significantly more" determination articulated in the Alice/Mayo test. Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 605, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1007 (2010). See MPEP § 2106.04(d) for more information about evaluating whether a claim reciting a judicial exception is integrated into a practical application and MPEP § 2106.05(b) and MPEP § 2106.05(c) for more information about how the machine-or-transformation test fits into the Alice/Mayo two-part framework. Likewise, eligibility should not be evaluated based on whether the claim recites a "useful, concrete, and tangible result," State Street Bank, 149 F.3d 1368, 1374, 47 USPQ2d 1596, 1602 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (quoting In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526, 1544, 31 USPQ2d 1545, 1557 (Fed. Cir. 1994)), as this test has been superseded. In re Bilski, 545 F.3d 943, 959-60, 88 USPQ2d 1385, 1394-95 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc), aff'd by Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 95 USPQ2d 1001 (2010). See also TLI Communications LLC v. AV Automotive LLC, 823 F.3d 607, 613, 118 USPQ2d 1744, 1748 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“It is well-settled that mere recitation of concrete, tangible components is insufficient to confer patent eligibility to an otherwise abstract idea”). The programmed computer or “special purpose computer” test of In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526, 31 USPQ2d 1545 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (i.e., the rationale that an otherwise ineligible algorithm or software could be made patent-eligible by merely adding a generic computer to the claim for the “special purpose” of executing the algorithm or software) was also superseded by the Supreme Court’s Bilski and Alice Corp. decisions. Eon Corp. IP Holdings LLC v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 785 F.3d 616, 623, 114 USPQ2d 1711, 1715 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (“[W]e note that Alappat has been superseded by Bilski, 561 U.S. at 605–06, and Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 110 USPQ2d 1976 (2014)”); Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Capital One Bank (USA), N.A., 792 F.3d 1363, 1366, 115 USPQ2d 1636, 1639 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (“An abstract idea does not become nonabstract by limiting the invention to a particular field of use or technological environment, such as the Internet [or] a computer”). Lastly, eligibility should not be evaluated based on whether the claimed invention has utility, because “[u]tility is not the test for patent-eligible subject matter.” Genetic Techs. Ltd. v. Merial LLC, 818 F.3d 1369, 1380, 118 USPQ2d 1541, 1548 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

Examiners are reminded that 35 U.S.C. 101 is not the sole tool for determining patentability; 35 U.S.C. 112 , 35 U.S.C. 102, and 35 U.S.C. 103 will provide additional tools for ensuring that the claim meets the conditions for patentability. As the Supreme Court made clear in Bilski, 561 U.S. at 602, 95 USPQ2d at 1006:

II. ESTABLISH BROADEST REASONABLE INTERPRETATION OF CLAIM AS A WHOLEThe § 101 patent-eligibility inquiry is only a threshold test. Even if an invention qualifies as a process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, in order to receive the Patent Act’s protection the claimed invention must also satisfy ‘‘the conditions and requirements of this title.’’ § 101. Those requirements include that the invention be novel, see § 102, nonobvious, see § 103, and fully and particularly described, see § 112.

It is essential that the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) of the claim be established prior to examining a claim for eligibility. The BRI sets the boundaries of the coverage sought by the claim and will influence whether the claim seeks to cover subject matter that is beyond the four statutory categories or encompasses subject matter that falls within the exceptions. See MyMail, Ltd. v. ooVoo, LLC, 934 F.3d 1373, 1379, 2019 USPQ2d 305789 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (“Determining patent eligibility requires a full understanding of the basic character of the claimed subject matter”), citing Bancorp Servs., LLC v. Sun Life Assurance Co. of Can. (U.S.), 687 F.3d 1266, 1273-74, 103 USPQ2d 1425, 1430 (Fed. Cir. 2012); In re Bilski, 545 F.3d 943, 951, 88 USPQ2d 1385, 1388 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc ), aff'd by Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 95 USPQ2d 1001 (2010) (“claim construction … is an important first step in a § 101 analysis”). Evaluating eligibility based on the BRI also ensures that patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. 101 does not depend simply on the draftsman’s art. Alice, 573 U.S. 208, 224, 110 USPQ2d at 1984, 1985 (citing Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 593, 198 USPQ 193, 198 (1978) and Mayo, 566 U.S. at 72, 101 USPQ2d at 1966). See MPEP § 2111 for more information about determining the BRI.

Claim interpretation affects the evaluation of both criteria for eligibility. For example, in Mentor Graphics v. EVE-USA, Inc., 851 F.3d 1275, 112 USPQ2d 1120 (Fed. Cir. 2017), claim interpretation was crucial to the court’s determination that claims to a “machine-readable medium” were not to a statutory category. In Mentor Graphics, the court interpreted the claims in light of the specification, which expressly defined the medium as encompassing “any data storage device” including random-access memory and carrier waves. Although random-access memory and magnetic tape are statutory media, carrier waves are not because they are signals similar to the transitory, propagating signals held to be non-statutory in Nuijten. 851 F.3d at 1294, 112 USPQ2d at 1133 (citing In re Nuijten, 500 F.3d 1346, 84 USPQ2d 1495 (Fed. Cir. 2007)). Accordingly, because the BRI of the claims covered both subject matter that falls within a statutory category (the random-access memory), as well as subject matter that does not (the carrier waves), the claims as a whole were not to a statutory category and thus failed the first criterion for eligibility.

With regard to the second criterion for eligibility, the Alice/Mayo test, claim interpretation can affect the first part of the test (whether the claims are directed to a judicial exception). For example, the patentee in Synopsys argued that the claimed methods of logic circuit design were intended to be used in conjunction with computer-based design tools, and were thus not mental processes. Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1147-49, 120 USPQ2d 1473, 1480-81 (Fed. Cir. 2016). The court disagreed, because it interpreted the claims as encompassing nothing other than pure mental steps (and thus falling within an abstract idea grouping) because the claims did not include any limitations requiring computer implementation. In contrast, the patentee in Enfish argued that its claimed self-referential table for a computer database was an improvement in an existing technology and thus not directed to an abstract idea. Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1336-37, 118 USPQ2d 1684, 1689-90 (Fed. Cir. 2016). The court agreed with the patentee, based on its interpretation of the claimed “means for configuring” under 35 U.S.C. 112(f) as requiring a four-step algorithm that achieved the improvements, as opposed to merely any form of storing tabular data. See also McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America, Inc. 837 F.3d 1299, 1314, 120 USPQ2d 1091, 1102 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (the claim’s construction incorporated rules of a particular type that improved an existing technological process). Claim interpretation can also affect the second part of the Alice/Mayo test (whether the claim recites additional elements that amount to significantly more than the judicial exception). For example, in Amdocs (Israel) Ltd. v. Openet Telecom, Inc., where the court relied on the construction of the term “enhance” (to require application of a number of field enhancements in a distributed fashion) to determine that the claim entails an unconventional technical solution to a technological problem. 841 F.3d 1288, 1300-01, 120 USPQ2d 1527, 1537 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

III. SUMMARY OF ANALYSIS AND FLOWCHART

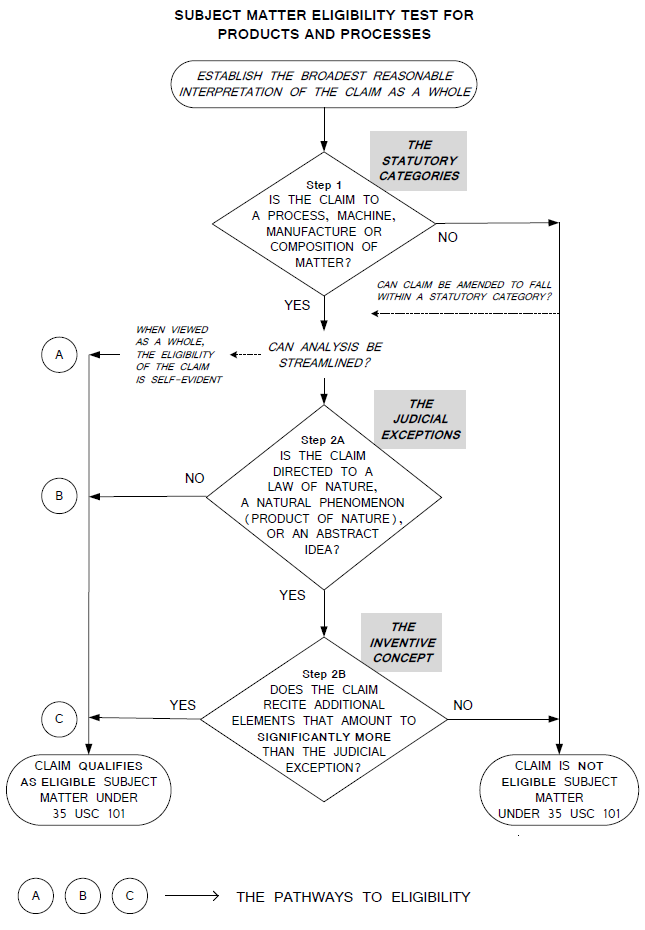

Examiners should determine whether a claim satisfies the criteria for subject matter eligibility by evaluating the claim in accordance with the following flowchart. The flowchart illustrates the steps of the subject matter eligibility analysis for products and processes that are to be used during examination for evaluating whether a claim is drawn to patent-eligible subject matter. It is recognized that under the controlling legal precedent there may be variations in the precise contours of the analysis for subject matter eligibility that will still achieve the same end result. The analysis set forth herein promotes examination efficiency and consistency across all technologies.

As shown in the flowchart, Step 1 relates to the statutory categories and ensures that the first criterion is met by confirming that the claim falls within one of the four statutory categories of invention. See MPEP § 2106.03 for more information on Step 1. Step 2, which is the Supreme Court’s Alice/Mayo test, is a two-part test to identify claims that are directed to a judicial exception (Step 2A) and to then evaluate if additional elements of the claim provide an inventive concept (Step 2B) (also called "significantly more" than the recited judicial exception). See MPEP § 2106.04 for more information on Step 2A and MPEP § 2106.05 for more information on Step 2B.

The flowchart also shows three pathways (A, B, and C) to eligibility:

Claims that could have been found eligible at Pathway A (streamlined analysis), but are subjected to further analysis at Steps 2A or Step 2B, will ultimately be found eligible at Pathways B or C. Thus, if the examiner is uncertain about whether a streamlined analysis is appropriate, the examiner is encouraged to conduct a full eligibility analysis. However, if the claim is not found eligible at any of Pathways A, B or C, the claim is patent ineligible and should be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 101.

Regardless of whether a rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 is made, a complete examination should be made for every claim under each of the other patentability requirements: 35 U.S.C. 102, 103, 112, and 101 (utility, inventorship and double patenting) and non-statutory double patenting. MPEP § 2103.

35 U.S.C. 101 enumerates four categories of subject matter that Congress deemed to be appropriate subject matter for a patent: processes, machines, manufactures and compositions of matter. As explained by the courts, these “four categories together describe the exclusive reach of patentable subject matter. If a claim covers material not found in any of the four statutory categories, that claim falls outside the plainly expressed scope of § 101 even if the subject matter is otherwise new and useful.” In re Nuijten, 500 F.3d 1346, 1354, 84 USPQ2d 1495, 1500 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

A process defines “actions”, i.e., an invention that is claimed as an act or step, or a series of acts or steps. As explained by the Supreme Court, a “process” is “a mode of treatment of certain materials to produce a given result. It is an act, or a series of acts, performed upon the subject-matter to be transformed and reduced to a different state or thing.” Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 70, 175 USPQ 673, 676 (1972) (italics added) (quoting Cochrane v. Deener, 94 U.S. 780, 788, 24 L. Ed. 139, 141 (1876)). See also Nuijten, 500 F.3d at 1355, 84 USPQ2d at 1501 (“The Supreme Court and this court have consistently interpreted the statutory term ‘process’ to require action”); NTP, Inc. v. Research in Motion, Ltd., 418 F.3d 1282, 1316, 75 USPQ2d 1763, 1791 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (“[A] process is a series of acts.”) (quoting Minton v. Natl. Ass’n. of Securities Dealers, 336 F.3d 1373, 1378, 67 USPQ2d 1614, 1681 (Fed. Cir. 2003)). As defined in 35 U.S.C. 100(b), the term “process” is synonymous with “method.”

The other three categories (machines, manufactures and compositions of matter) define the types of physical or tangible “things” or “products” that Congress deemed appropriate to patent. Digitech Image Techs. v. Electronics for Imaging, 758 F.3d 1344, 1348, 111 USPQ2d 1717, 1719 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (“For all categories except process claims, the eligible subject matter must exist in some physical or tangible form.”). Thus, when determining whether a claimed invention falls within one of these three categories, examiners should verify that the invention is to at least one of the following categories and is claimed in a physical or tangible form.

It is not necessary to identify a single category into which a claim falls, so long as it is clear that the claim falls into at least one category. For example, because a microprocessor is generally understood to be a manufacture, a product claim to the microprocessor or a system comprising the microprocessor satisfies Step 1 regardless of whether the claim falls within any other statutory category (such as a machine). It is also not necessary to identify a “correct” category into which the claim falls, because although in many instances it is clear within which category a claimed invention falls, a claim may satisfy the requirements of more than one category. For example, a bicycle satisfies both the machine and manufacture categories, because it is a tangible product that is concrete and consists of parts such as a frame and wheels (thus satisfying the machine category), and it is an article that was produced from raw materials such as aluminum ore and liquid rubber by giving them a new form (thus satisfying the manufacture category). Similarly, a genetically modified bacterium satisfies both the composition of matter and manufacture categories, because it is a tangible product that is a combination of two or more substances such as proteins, carbohydrates and other chemicals (thus satisfying the composition of matter category), and it is an article that was genetically modified by humans to have new properties such as the ability to digest multiple types of hydrocarbons (thus satisfying the manufacture category).

Non-limiting examples of claims that are not directed to any of the statutory categories include:

As the courts' definitions of machines, manufactures and compositions of matter indicate, a product must have a physical or tangible form in order to fall within one of these statutory categories. Digitech, 758 F.3d at 1348, 111 USPQ2d at 1719. Thus, the Federal Circuit has held that a product claim to an intangible collection of information, even if created by human effort, does not fall within any statutory category. Digitech, 758 F.3d at 1350, 111 USPQ2d at 1720 (claimed “device profile” comprising two sets of data did not meet any of the categories because it was neither a process nor a tangible product). Similarly, software expressed as code or a set of instructions detached from any medium is an idea without physical embodiment. See Microsoft Corp. v. AT&T Corp., 550 U.S. 437, 449, 82 USPQ2d 1400, 1407 (2007); see also Benson, 409 U.S. 67, 175 USPQ2d 675 (An "idea" is not patent eligible). Thus, a product claim to a software program that does not also contain at least one structural limitation (such as a “means plus function” limitation) has no physical or tangible form, and thus does not fall within any statutory category. Another example of an intangible product that does not fall within a statutory category is a paradigm or business model for a marketing company. In re Ferguson, 558 F.3d 1359, 1364, 90 USPQ2d 1035, 1039-40 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

Even when a product has a physical or tangible form, it may not fall within a statutory category. For instance, a transitory signal, while physical and real, does not possess concrete structure that would qualify as a device or part under the definition of a machine, is not a tangible article or commodity under the definition of a manufacture (even though it is man-made and physical in that it exists in the real world and has tangible causes and effects), and is not composed of matter such that it would qualify as a composition of matter. Nuijten, 500 F.3d at 1356-1357, 84 USPQ2d at 1501-03. As such, a transitory, propagating signal does not fall within any statutory category. Mentor Graphics Corp. v. EVE-USA, Inc., 851 F.3d 1275, 1294, 112 USPQ2d 1120, 1133 (Fed. Cir. 2017); Nuijten, 500 F.3d at 1356-1357, 84 USPQ2d at 1501-03.

II. ELIGIBILITY STEP 1: WHETHER A CLAIM IS TO A STATUTORY CATEGORY

As described in MPEP § 2106, subsection III, Step 1 of the eligibility analysis asks: Is the claim to a process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter? Like the other steps in the eligibility analysis, evaluation of this step should be made after determining what the inventor has invented by reviewing the entire application disclosure and construing the claims in accordance with their broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI). See MPEP § 2106, subsection II, for more information about the importance of understanding what has been invented, and MPEP § 2111 for more information about the BRI.

In the context of the flowchart in MPEP § 2106, subsection III, Step 1 determines whether:

A claim whose BRI covers both statutory and non-statutory embodiments embraces subject matter that is not eligible for patent protection and therefore is directed to non-statutory subject matter. Such claims fail the first step (Step 1: NO) and should be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 101, for at least this reason. In such a case, it is a best practice for the examiner to point out the BRI and recommend an amendment, if possible, that would narrow the claim to those embodiments that fall within a statutory category.

For example, the BRI of machine readable media can encompass non-statutory transitory forms of signal transmission, such as a propagating electrical or electromagnetic signal per se. See In re Nuijten, 500 F.3d 1346, 84 USPQ2d 1495 (Fed. Cir. 2007). When the BRI encompasses transitory forms of signal transmission, a rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 as failing to claim statutory subject matter would be appropriate. Thus, a claim to a computer readable medium that can be a compact disc or a carrier wave covers a non-statutory embodiment and therefore should be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 101 as being directed to non-statutory subject matter. See, e.g., Mentor Graphics v. EVE-USA, Inc., 851 F.3d at 1294-95, 112 USPQ2d at 1134 (claims to a “machine-readable medium” were non-statutory, because their scope encompassed both statutory random-access memory and non-statutory carrier waves).

If a claim is clearly not within one of the four categories (Step 1: NO), then a rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 must be made indicating that the claim is directed to non-statutory subject matter. Form paragraphs 7.05 and 7.05.01 should be used; see MPEP § 2106.07(a)(1). However, as shown in the flowchart in MPEP § 2106 subsection III, when a claim fails under Step 1 (Step 1: NO), but it appears from applicant’s disclosure that the claim could be amended to fall within a statutory category (Step 1: YES), the analysis should proceed to determine whether such an amended claim would qualify as eligible at Pathway A, B or C. In such a case, it is a best practice for the examiner to recommend an amendment, if possible, that would resolve eligibility of the claim.

Determining that a claim falls within one of the four enumerated categories of patentable subject matter recited in 35 U.S.C. 101 (i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter) in Step 1 does not end the eligibility analysis, because claims directed to nothing more than abstract ideas (such as a mathematical formula or equation), natural phenomena, and laws of nature are not eligible for patent protection. Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 185, 209 USPQ 1, 7 (1981). Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int'l, 573 U.S. 208, 216, 110 USPQ2d 1976, 1980 (2014) (citing Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576, 589, 106 USPQ2d 1972, 1979 (2013)); Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303, 309, 206 USPQ 193, 197 (1980); Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 589, 198 USPQ 193, 197 (1978); Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 67-68, 175 USPQ 673, 675 (1972). See also Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 601, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1005-06 (2010) (“The Court’s precedents provide three specific exceptions to § 101's broad patent-eligibility principles: ‘laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas’”) (quoting Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. at 309, 206 USPQ at 197 (1980)).

In addition to the terms “laws of nature,” “natural phenomena,” and “abstract ideas,” judicially recognized exceptions have been described using various other terms, including “physical phenomena,” “products of nature,” “scientific principles,” “systems that depend on human intelligence alone,” “disembodied concepts,” “mental processes,” and “disembodied mathematical algorithms and formulas.” It should be noted that there are no bright lines between the types of exceptions, and that many of the concepts identified by the courts as exceptions can fall under several exceptions. For example, mathematical formulas are considered to be a judicial exception as they express a scientific truth, but have been labelled by the courts as both abstract ideas and laws of nature. Likewise, “products of nature” are considered to be an exception because they tie up the use of naturally occurring things, but have been labelled as both laws of nature and natural phenomena. Thus, it is sufficient for this analysis for the examiner to identify that the claimed concept (the specific claim limitation(s) that the examiner believes may recite an exception) aligns with at least one judicial exception.

The Supreme Court has explained that the judicial exceptions reflect the Court’s view that abstract ideas, laws of nature, and natural phenomena are “the basic tools of scientific and technological work”, and are thus excluded from patentability because “monopolization of those tools through the grant of a patent might tend to impede innovation more than it would tend to promote it.” Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 216, 110 USPQ2d at 1980 (quoting Myriad, 569 U.S. at 589, 106 USPQ2d at 1978 and Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs. Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 71, 101 USPQ2d 1961, 1965 (2012)). The Supreme Court’s concern that drives this “exclusionary principle” is pre-emption. Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 216, 110 USPQ2d at 1980. The Court has held that a claim may not preempt abstract ideas, laws of nature, or natural phenomena, even if the judicial exception is narrow (e.g., a particular mathematical formula such as the Arrhenius equation). See, e.g., Mayo, 566 U.S. at 79-80, 86-87, 101 USPQ2d at 1968-69, 1971 (claims directed to “narrow laws that may have limited applications” held ineligible); Flook, 437 U.S. at 589-90, 198 USPQ at 197 (claims that did not “wholly preempt the mathematical formula” held ineligible). This is because such a patent would “in practical effect [] be a patent on the [abstract idea, law of nature or natural phenomenon] itself.” Benson, 409 U.S. at 71- 72, 175 USPQ at 676. The concern over preemption was expressed as early as 1852. See Le Roy v. Tatham, 55 U.S. (14 How.) 156, 175 (1852) (“A principle, in the abstract, is a fundamental truth; an original cause; a motive; these cannot be patented, as no one can claim in either of them an exclusive right.”).

While preemption is the concern underlying the judicial exceptions, it is not a standalone test for determining eligibility. Rapid Litig. Mgmt. v. CellzDirect, Inc., 827 F.3d 1042, 1052, 119 USPQ2d 1370, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2016). Instead, questions of preemption are inherent in and resolved by the two-part framework from Alice Corp. and Mayo (the Alice/Mayo test referred to by the Office as Steps 2A and 2B). Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1150, 120 USPQ2d 1473, 1483 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., 788 F.3d 1371, 1379, 115 USPQ2d 1152, 1158 (Fed. Cir. 2015). It is necessary to evaluate eligibility using the Alice/Mayo test, because while a preemptive claim may be ineligible, the absence of complete preemption does not demonstrate that a claim is eligible. Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 191-92 n.14, 209 USPQ 1, 10-11 n.14 (1981) (“We rejected in Flook the argument that because all possible uses of the mathematical formula were not pre-empted, the claim should be eligible for patent protection”). See also Synopsys v. Mentor Graphics, 839 F.3d at 1150, 120 USPQ2d at 1483; FairWarning IP, LLC v. Iatric Sys., Inc., 839 F.3d 1089, 1098, 120 USPQ2d 1293, 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Symantec Corp., 838 F.3d 1307, 1320-21, 120 USPQ2d 1353, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Sequenom, 788 F.3d at 1379, 115 USPQ2d at 1158. Several Federal Circuit decisions, however, have noted the absence of preemption when finding claims eligible under the Alice/Mayo test. McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games Am. Inc., 837 F.3d 1299, 1315, 120 USPQ2d 1091, 1102-03 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Rapid Litig. Mgmt. v. CellzDirect, Inc., 827 F.3d 1042, 1052, 119 USPQ2d 1370, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2016); BASCOM Global Internet v. AT&T Mobility, LLC, 827 F.3d 1341, 1350-52, 119 USPQ2d 1236, 1243-44 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

The Supreme Court’s decisions make it clear that judicial exceptions need not be old or long-prevalent, and that even newly discovered or novel judicial exceptions are still exceptions. For example, the mathematical formula in Flook, the laws of nature in Mayo, and the isolated DNA in Myriad were all novel or newly discovered, but nonetheless were considered by the Supreme Court to be judicial exceptions because they were “‘basic tools of scientific and technological work’ that lie beyond the domain of patent protection.” Myriad, 569 U.S. 576, 589, 106 USPQ2d at 1976, 1978 (noting that Myriad discovered the BRCA1 and BRCA1 genes and quoting Mayo, 566 U.S. 71, 101 USPQ2d at 1965); Flook, 437 U.S. at 591-92, 198 USPQ2d at 198 (“the novelty of the mathematical algorithm is not a determining factor at all”); Mayo, 566 U.S. 73-74, 78, 101 USPQ2d 1966, 1968 (noting that the claims embody the researcher's discoveries of laws of nature). The Supreme Court’s cited rationale for considering even “just discovered” judicial exceptions as exceptions stems from the concern that “without this exception, there would be considerable danger that the grant of patents would ‘tie up’ the use of such tools and thereby ‘inhibit future innovation premised upon them.’” Myriad, 569 U.S. at 589, 106 USPQ2d at 1978-79 (quoting Mayo, 566 U.S. at 86, 101 USPQ2d at 1971). See also Myriad, 569 U.S. at 591, 106 USPQ2d at 1979 (“Groundbreaking, innovative, or even brilliant discovery does not by itself satisfy the §101 inquiry.”). The Federal Circuit has also applied this principle, for example, when holding a concept of using advertising as an exchange or currency to be an abstract idea, despite the patentee’s arguments that the concept was “new”. Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, 772 F.3d 709, 714-15, 112 USPQ2d 1750, 1753-54 (Fed. Cir. 2014). Cf. Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1151, 120 USPQ2d 1473, 1483 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“a new abstract idea is still an abstract idea”) (emphasis in original).

For a detailed discussion of abstract ideas, see MPEP § 2106.04(a); for a detailed discussion of laws of nature, natural phenomena and products of nature, see MPEP § 2106.04(b).

II. ELIGIBILITY STEP 2A: WHETHER A CLAIM IS DIRECTED TO A JUDICIAL EXCEPTION

As described in MPEP § 2106, subsection III, Step 2A of the Office’s eligibility analysis is the first part of the Alice/Mayo test, i.e., the Supreme Court’s “framework for distinguishing patents that claim laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas from those that claim patent-eligible applications of those concepts.” Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int'l, 573 U.S. 208, 217-18, 110 USPQ2d 1976, 1981 (2014) (citing Mayo, 566 U.S. at 77-78, 101 USPQ2d at 1967-68). Like the other steps in the eligibility analysis, evaluation of this step should be made after determining what the inventor has invented by reviewing the entire application disclosure and construing the claims in accordance with their broadest reasonable interpretation. See MPEP § 2106, subsection II for more information about the importance of understanding what has been invented, and MPEP § 2111 for more information about the broadest reasonable interpretation.

Step 2A asks: Is the claim directed to a law of nature, a natural phenomenon (product of nature) or an abstract idea? In the context of the flowchart in MPEP § 2106, subsection III, Step 2A determines whether:

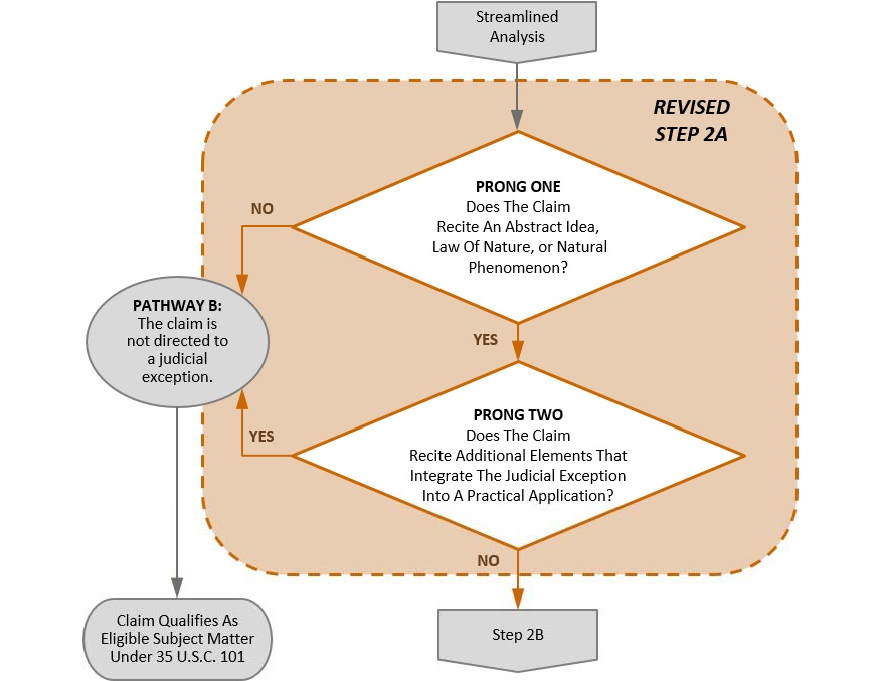

Step 2A is a two-prong inquiry, in which examiners determine in Prong One whether a claim recites a judicial exception, and if so, then determine in Prong Two if the recited judicial exception is integrated into a practical application of that exception. Together, these prongs represent the first part of the Alice/Mayo test, which determines whether a claim is directed to a judicial exception.

The flowchart below depicts the two-prong analysis that is performed in order to answer the Step 2A inquiry.

Prong One asks does the claim recite an abstract idea, law of nature, or natural phenomenon? In Prong One examiners evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception, i.e. whether a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea is set forth or described in the claim. While the terms "set forth" and "described" are thus both equated with "recite", their different language is intended to indicate that there are two ways in which an exception can be recited in a claim. For instance, the claims in Diehr, 450 U.S. at 178 n. 2, 179 n.5, 191-92, 209 USPQ at 4-5 (1981), clearly stated a mathematical equation in the repetitively calculating step, and the claims in Mayo, 566 U.S. 66, 75-77, 101 USPQ2d 1961, 1967-68 (2012), clearly stated laws of nature in the wherein clause, such that the claims “set forth” an identifiable judicial exception. Alternatively, the claims in Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 218, 110 USPQ2d at 1982, described the concept of intermediated settlement without ever explicitly using the words “intermediated” or “settlement.”

The Supreme Court has held that Section 101 contains an implicit exception for ‘‘[l]aws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas,’’ which are ‘‘the basic tools of scientific and technological work.’’ Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 216, 110 USPQ2d at 1980 (citing Mayo, 566 US at 71, 101 USPQ2d at 1965). Yet, the Court has explained that ‘‘[a]t some level, all inventions embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas,’’ and has cautioned ‘‘to tread carefully in construing this exclusionary principle lest it swallow all of patent law.’’ Id. See also Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1335, 118 USPQ2d 1684, 1688 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“The ‘directed to’ inquiry, therefore, cannot simply ask whether the claims involve a patent-ineligible concept, because essentially every routinely patent-eligible claim involving physical products and actions involves a law of nature and/or natural phenomenon”). Examiners should accordingly be careful to distinguish claims that recite an exception (which require further eligibility analysis) and claims that merely involve an exception (which are eligible and do not require further eligibility analysis).

An example of a claim that recites a judicial exception is “A machine comprising elements that operate in accordance with F=ma.” This claim sets forth the principle that force equals mass times acceleration (F=ma) and therefore recites a law of nature exception. Because F=ma represents a mathematical formula, the claim could alternatively be considered as reciting an abstract idea. Because this claim recites a judicial exception, it requires further analysis in Prong Two in order to answer the Step 2A inquiry. An example of a claim that merely involves, or is based on, an exception is a claim to “A teeter-totter comprising an elongated member pivotably attached to a base member, having seats and handles attached at opposing sides of the elongated member.” This claim is based on the concept of a lever pivoting on a fulcrum, which involves the natural principles of mechanical advantage and the law of the lever. However, this claim does not recite these natural principles and therefore is not directed to a judicial exception (Step 2A: NO). Thus, the claim is eligible at Pathway B without further analysis.

If the claim recites a judicial exception (i.e., an abstract idea enumerated in MPEP § 2106.04(a), a law of nature, or a natural phenomenon), the claim requires further analysis in Prong Two. If the claim does not recite a judicial exception (a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea), then the claim cannot be directed to a judicial exception (Step 2A: NO), and thus the claim is eligible at Pathway B without further analysis.

For more information how to determine if a claim recites an abstract idea, see MPEP § 2106.04(a). For more information on how to determine if a claim recites a law of nature or natural phenomenon, see MPEP § 2106.04(b). For more information on how to determine if a claim recites a product of nature, see MPEP § 2106.04(c).

2. Prong Two

Prong Two asks does the claim recite additional elements that integrate the judicial exception into a practical application? In Prong Two, examiners evaluate whether the claim as a whole integrates the exception into a practical application of that exception. If the additional elements in the claim integrate the recited exception into a practical application of the exception, then the claim is not directed to the judicial exception (Step 2A: NO) and thus is eligible at Pathway B. This concludes the eligibility analysis. If, however, the additional elements do not integrate the exception into a practical application, then the claim is directed to the recited judicial exception (Step 2A: YES), and requires further analysis under Step 2B (where it may still be eligible if it amounts to an ‘‘inventive concept’’). For more information on how to evaluate whether a judicial exception is integrated into a practical application, see MPEP § 2106.04(d)(2).

The mere inclusion of a judicial exception such as a mathematical formula (which is one of the mathematical concepts identified as an abstract idea in MPEP § 2106.04(a)) in a claim means that the claim “recites” a judicial exception under Step 2A Prong One. However, mere recitation of a judicial exception does not mean that the claim is “directed to” that judicial exception under Step 2A Prong Two. Instead, under Prong Two, a claim that recites a judicial exception is not directed to that judicial exception, if the claim as a whole integrates the recited judicial exception into a practical application of that exception. Prong Two thus distinguishes claims that are “directed to” the recited judicial exception from claims that are not “directed to” the recited judicial exception.

Because a judicial exception is not eligible subject matter, Bilski, 561 U.S. at 601, 95 USPQ2d at 1005-06 (quoting Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. at 309, 206 USPQ at 197 (1980)), if there are no additional claim elements besides the judicial exception, or if the additional claim elements merely recite another judicial exception, that is insufficient to integrate the judicial exception into a practical application. See, e.g., RecogniCorp, LLC v. Nintendo Co., 855 F.3d 1322, 1327, 122 USPQ2d 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (“Adding one abstract idea (math) to another abstract idea (encoding and decoding) does not render the claim non-abstract”); Genetic Techs. v. Merial LLC, 818 F.3d 1369, 1376, 118 USPQ2d 1541, 1546 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (eligibility “cannot be furnished by the unpatentable law of nature (or natural phenomenon or abstract idea) itself.”). For a claim reciting a judicial exception to be eligible, the additional elements (if any) in the claim must “transform the nature of the claim” into a patent-eligible application of the judicial exception, Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 217, 110 USPQ2d at 1981, either at Prong Two or in Step 2B. If there are no additional elements in the claim, then it cannot be eligible. In such a case, after making the appropriate rejection (see MPEP § 2106.07 for more information on formulating a rejection for lack of eligibility), it is a best practice for the examiner to recommend an amendment, if possible, that would resolve eligibility of the claim.

B.Evaluating Claims Reciting Multiple Judicial Exceptions

A claim may recite multiple judicial exceptions. For example, claim 4 at issue in Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 95 USPQ2d 1001 (2010) recited two abstract ideas, and the claims at issue in Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs. Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 101 USPQ2d 1961 (2012) recited two laws of nature. However, these claims were analyzed by the Supreme Court in the same manner as claims reciting a single judicial exception, such as those in Alice Corp., 573 U.S. 208, 110 USPQ2d 1976.

During examination, examiners should apply the same eligibility analysis to all claims regardless of the number of exceptions recited therein. Unless it is clear that a claim recites distinct exceptions, such as a law of nature and an abstract idea, care should be taken not to parse the claim into multiple exceptions, particularly in claims involving abstract ideas. Accordingly, if possible examiners should treat the claim for Prong Two and Step 2B purposes as containing a single judicial exception.

In some claims, the multiple exceptions are distinct from each other, e.g., a first limitation describes a law of nature, and a second limitation elsewhere in the claim recites an abstract idea. In these cases, for purposes of examination efficiency, examiners should select one of the exceptions and conduct the eligibility analysis for that selected exception. If the analysis indicates that the claim recites an additional element or combination of elements that integrate the selected exception into a practical application or that amount to significantly more than the selected exception, then the claim should be considered patent eligible. On the other hand, if the claim does not recite any additional element or combination of elements that integrate the selected exception into a practical application, and also does not recite any additional element or combination of elements that amounts to significantly more than the selected exception, then the claim should be considered ineligible. University of Utah Research Foundation v. Ambry Genetics, 774 F.3d 755, 762, 113 USPQ2d 1241, 1246 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (because claims did not amount to significantly more than the recited abstract idea, court “need not decide” if claims also recited a law of nature).

In other claims, multiple abstract ideas, which may fall in the same or different groupings, or multiple laws of nature may be recited. In these cases, examiners should not parse the claim. For example, in a claim that includes a series of steps that recite mental steps as well as a mathematical calculation, an examiner should identify the claim as reciting both a mental process and a mathematical concept for Step 2A Prong One to make the analysis clear on the record. However, if possible, the examiner should consider the limitations together as a single abstract idea for Step 2A Prong Two and Step 2B (if necessary) rather than as a plurality of separate abstract ideas to be analyzed individually.

The abstract idea exception has deep roots in the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence. See Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 601-602, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1006 (2010) (citing Le Roy v. Tatham, 55 U.S. (14 How.) 156, 174–175 (1853)). Despite this long history, the courts have declined to define abstract ideas. However, it is clear from the body of judicial precedent that software and business methods are not excluded categories of subject matter. For example, the Supreme Court concluded that business methods are not “categorically outside of § 101's scope,” stating that “a business method is simply one kind of ‘method’ that is, at least in some circumstances, eligible for patenting under § 101.” Bilski, 561 U.S. at 607, 95 USPQ2d at 1008 (2010). See also Content Extraction and Transmission, LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, 776 F.3d 1343, 1347, 113 USPQ2d 1354, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (“there is no categorical business-method exception”). Likewise, software is not automatically an abstract idea, even if performance of a software task involves an underlying mathematical calculation or relationship. See, e.g., Thales Visionix, Inc. v. United States, 850 F.3d 1343, 121 USPQ2d 1898, 1902 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (“That a mathematical equation is required to complete the claimed method and system does not doom the claims to abstraction.”); McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games Am. Inc., 837 F.3d 1299, 1316, 120 USPQ2d 1091, 1103 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (methods of automatic lip synchronization and facial expression animation using computer-implemented rules were not directed to an abstract idea); Enfish, 822 F.3d 1327, 1336, 118 USPQ2d 1684, 1689 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (claims to self-referential table for a computer database were not directed to an abstract idea).

To facilitate examination, the Office has set forth an approach to identifying abstract ideas that distills the relevant case law into enumerated groupings of abstract ideas. The enumerated groupings are firmly rooted in Supreme Court precedent as well as Federal Circuit decisions interpreting that precedent, as is explained in MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2). This approach represents a shift from the former case-comparison approach that required examiners to rely on individual judicial cases when determining whether a claim recites an abstract idea. By grouping the abstract ideas, the examiners’ focus has been shifted from relying on individual cases to generally applying the wide body of case law spanning all technologies and claim types.

The enumerated groupings of abstract ideas are defined as:

Examiners should determine whether a claim recites an abstract idea by (1) identifying the specific limitation(s) in the claim under examination that the examiner believes recites an abstract idea, and (2) determining whether the identified limitations(s) fall within at least one of the groupings of abstract ideas listed above. The groupings of abstract ideas, and their relationship to the body of judicial precedent, are further discussed in MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2).

If the identified limitation(s) falls within at least one of the groupings of abstract ideas, it is reasonable to conclude that the claim recites an abstract idea in Step 2A Prong One. The claim then requires further analysis in Step 2A Prong Two, to determine whether any additional elements in the claim integrate the abstract idea into a practical application, see MPEP § 2106.04(d).

If the identified limitation(s) do not fall within any of the groupings of abstract ideas, it is reasonable to find that the claim does not recite an abstract idea. This concludes the abstract idea judicial exception eligibility analysis, except in the rare circumstance discussed in MPEP § 2106.04(a)(3), below. The claim is thus eligible at Pathway B unless the claim recites, and is directed to, another exception (such as a law of nature or natural phenomenon).

If the claims recites another judicial exception (i.e. law of nature or natural phenomenon), see MPEP §§ 2106.04(b) and 2106.04(c) for more information on Step 2A analysis.

MPEP § 2106.04(a)(1) provides examples of claims that do not recite abstract ideas (or other judicial exceptions) and thus are eligible at Step 2A Prong One.

MPEP § 2106.04(a)(2) provides further explanation on the abstract idea groupings. It should be noted that these groupings are not mutually exclusive, i.e., some claims recite limitations that fall within more than one grouping or sub-grouping. For example, a claim reciting performing mathematical calculations using a formula that could be practically performed in the human mind may be considered to fall within the mathematical concepts grouping and the mental process grouping. Accordingly, examiners should identify at least one abstract idea grouping, but preferably identify all groupings to the extent possible, if a claim limitation(s) is determined to fall within multiple groupings and proceed with the analysis in Step 2A Prong Two.

When evaluating a claim to determine whether it recites an abstract idea, examiners should keep in mind that while “all inventions at some level embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract ideas”, not all claims recite an abstract idea. See Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank, Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 217, 110 USPQ2d 1976, 1980-81 (2014) (citing Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs. Inc., 566 US 66, 71, 101 USPQ2d 1961, 1965 (2012)). The Step 2A Prong One analysis articulated in MPEP § 2106.04 accounts for this cautionary principle by requiring a claim to recite (i.e., set forth or describe) an abstract idea in Prong One before proceeding to the Prong Two inquiry about whether the claim is directed to that idea, thereby separating claims reciting abstract ideas from those that are merely based on or involve an abstract idea.

Some claims are not directed to an abstract idea because they do not recite an abstract idea, although it may be apparent that at some level they are based on or involve an abstract idea. Because these claims do not recite an abstract idea (or other judicial exception), they are eligible at Step 2A Prong One (Pathway B).

Non-limiting hypothetical examples of claims that do not recite (set forth or describe) an abstract idea include:

The mathematical concepts grouping is defined as mathematical relationships, mathematical formulas or equations, and mathematical calculations. The Supreme Court has identified a number of concepts falling within this grouping as abstract ideas including: a procedure for converting binary-coded decimal numerals into pure binary form, Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 65, 175 USPQ2d 673, 674 (1972); a mathematical formula for calculating an alarm limit, Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 588-89, 198 USPQ2d 193, 195 (1978); the Arrhenius equation, Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 191, 209 USPQ 1, 15 (1981); and a mathematical formula for hedging, Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 611, 95 USPQ 2d 1001, 1004 (2010).

The Court’s rationale for identifying these “mathematical concepts” as judicial exceptions is that a ‘‘mathematical formula as such is not accorded the protection of our patent laws,’’ Diehr, 450 U.S. at 191, 209 USPQ at 15 (citing Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 175 USPQ 673), and thus ‘‘the discovery of [a mathematical formula] cannot support a patent unless there is some other inventive concept in its application.’’ Flook, 437 U.S. at 594, 198 USPQ at 199. In the past, the Supreme Court sometimes described mathematical concepts as laws of nature, and at other times described these concepts as judicial exceptions without specifying a particular type of exception. See, e.g., Benson, 409 U.S. at 65, 175 USPQ2d at 674; Flook, 437 U.S. at 589, 198 USPQ2d at 197; Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co. v. Radio Corp. of Am., 306 U.S. 86, 94, 40 USPQ 199, 202 (1939) (‘‘[A] scientific truth, or the mathematical expression of it, is not patentable invention[.]’’). More recent opinions of the Supreme Court, however, have affirmatively characterized mathematical relationships and formulas as abstract ideas. See, e.g., Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 218, 110 USPQ2d 1976, 1981 (2014) (describing Flook as holding “that a mathematical formula for computing ‘alarm limits’ in a catalytic conversion process was also a patent-ineligible abstract idea.”); Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 611-12, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1010 (2010) (noting that the claimed “concept of hedging, described in claim 1 and reduced to a mathematical formula in claim 4, is an unpatentable abstract idea,”).

When determining whether a claim recites a mathematical concept (i.e., mathematical relationships, mathematical formulas or equations, and mathematical calculations), examiners should consider whether the claim recites a mathematical concept or merely limitations that are based on or involve a mathematical concept. A claim does not recite a mathematical concept (i.e., the claim limitations do not fall within the mathematical concept grouping), if it is only based on or involves a mathematical concept. See, e.g., Thales Visionix, Inc. v. United States, 850 F.3d 1343, 1348-49, 121 USPQ2d 1898, 1902-03 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (determining that the claims to a particular configuration of inertial sensors and a particular method of using the raw data from the sensors in order to more accurately calculate the position and orientation of an object on a moving platform did not merely recite “the abstract idea of using ‘mathematical equations for determining the relative position of a moving object to a moving reference frame’.”). For example, a limitation that is merely based on or involves a mathematical concept described in the specification may not be sufficient to fall into this grouping, provided the mathematical concept itself is not recited in the claim.

It is important to note that a mathematical concept need not be expressed in mathematical symbols, because “[w]ords used in a claim operating on data to solve a problem can serve the same purpose as a formula.” In re Grams, 888 F.2d 835, 837 and n.1, 12 USPQ2d 1824, 1826 and n.1 (Fed. Cir. 1989). See, e.g., SAP America, Inc. v. InvestPic, LLC, 898 F.3d 1161, 1163, 127 USPQ2d 1597, 1599 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (holding that claims to a ‘‘series of mathematical calculations based on selected information’’ are directed to abstract ideas); Digitech Image Techs., LLC v. Elecs. for Imaging, Inc., 758 F.3d 1344, 1350, 111 USPQ2d 1717, 1721 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (holding that claims to a ‘‘process of organizing information through mathematical correlations’’ are directed to an abstract idea); and Bancorp Servs., LLC v. Sun Life Assurance Co. of Can. (U.S.), 687 F.3d 1266, 1280, 103 USPQ2d 1425, 1434 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (identifying the concept of ‘‘managing a stable value protected life insurance policy by performing calculations and manipulating the results’’ as an abstract idea).

A. Mathematical Relationships

A mathematical relationship is a relationship between variables or numbers. A mathematical relationship may be expressed in words or using mathematical symbols. For example, pressure (p) can be described as the ratio between the magnitude of the normal force (F) and area of the surface on contact (A), or it can be set forth in the form of an equation such as p = F/A.

Examples of mathematical relationships recited in a claim include:

A claim that recites a numerical formula or equation will be considered as falling within the “mathematical concepts” grouping. In addition, there are instances where a formula or equation is written in text format that should also be considered as falling within this grouping. For example, the phrase “determining a ratio of A to B” is merely using a textual replacement for the particular equation (ratio = A/B). Additionally, the phrase “calculating the force of the object by multiplying its mass by its acceleration” is using a textual replacement for the particular equation (F= ma).

Examples of mathematical equations or formulas recited in a claim include:

A claim that recites a mathematical calculation, when the claim is given its broadest reasonable interpretation in light of the specification, will be considered as falling within the “mathematical concepts” grouping. A mathematical calculation is a mathematical operation (such as multiplication) or an act of calculating using mathematical methods to determine a variable or number, e.g., performing an arithmetic operation such as exponentiation. There is no particular word or set of words that indicates a claim recites a mathematical calculation. That is, a claim does not have to recite the word “calculating” in order to be considered a mathematical calculation. For example, a step of “determining” a variable or number using mathematical methods or “performing” a mathematical operation may also be considered mathematical calculations when the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim in light of the specification encompasses a mathematical calculation.

Examples of mathematical calculations recited in a claim include:

The phrase “methods of organizing human activity” is used to describe concepts relating to:

The Supreme Court has identified a number of concepts falling within the “certain methods of organizing human activity” grouping as abstract ideas. In particular, in Alice, the Court concluded that the use of a third party to mediate settlement risk is a ‘‘fundamental economic practice’’ and thus an abstract idea. 573 U.S. at 219–20, 110 USPQ2d at 1982. In addition, the Court in Alice described the concept of risk hedging identified as an abstract idea in Bilski as ‘‘a method of organizing human activity’’. Id. Previously, in Bilski, the Court concluded that hedging is a ‘‘fundamental economic practice’’ and therefore an abstract idea. 561 U.S. at 611–612, 95 USPQ2d at 1010.

The term “certain” qualifies the “certain methods of organizing human activity” grouping as a reminder of several important points. First, not all methods of organizing human activity are abstract ideas (e.g., “a defined set of steps for combining particular ingredients to create a drug formulation” is not a certain "method of organizing human activity”), In re Marco Guldenaar Holding B.V., 911 F.3d 1157, 1160-61, 129 USPQ2d 1008, 1011 (Fed. Cir. 2018). Second, this grouping is limited to activity that falls within the enumerated sub-groupings of fundamental economic principles or practices, commercial or legal interactions, and managing personal behavior and relationships or interactions between people, and is not to be expanded beyond these enumerated sub-groupings except in rare circumstances as explained in MPEP § 2106.04(a)(3). Finally, the sub-groupings encompass both activity of a single person (for example, a person following a set of instructions or a person signing a contract online) and activity that involves multiple people (such as a commercial interaction), and thus, certain activity between a person and a computer (for example a method of anonymous loan shopping that a person conducts using a mobile phone) may fall within the “certain methods of organizing human activity” grouping. It is noted that the number of people involved in the activity is not dispositive as to whether a claim limitation falls within this grouping. Instead, the determination should be based on whether the activity itself falls within one of the sub-groupings.

A.Fundamental Economic Practices or Principles

The courts have used the phrases “fundamental economic practices” or “fundamental economic principles” to describe concepts relating to the economy and commerce. Fundamental economic principles or practices include hedging, insurance, and mitigating risks.

The term “fundamental” is not used in the sense of necessarily being “old” or “well-known.” See, e.g., OIP Techs., Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 788 F.3d 1359, 1364, 115 U.S.P.Q.2d 1090, 1092 (Fed Cir. 2015) (a new method of price optimization was found to be a fundamental economic concept); In re Smith, 815 F.3d 816, 818-19, 118 USPQ2d 1245, 1247 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (describing a new set of rules for conducting a wagering game as a “fundamental economic practice”); In re Greenstein, 774 Fed. Appx. 661, 664, 2019 USPQ2d 212400 (Fed Cir. 2019) (non-precedential) (claims to a new method of allocating returns to different investors in an investment fund was a fundamental economic concept). However, being old or well-known may indicate that the practice is fundamental. See, e.g., Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 219-20, 110 USPQ2d 1981-82 (2014) (describing the concept of intermediated settlement, like the risk hedging in Bilski, to be a “‘fundamental economic practice long prevalent in our system of commerce’” and also as “a building block of the modern economy”) (citation omitted); Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 611, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1010 (2010) (claims to the concept of hedging are a “fundamental economic practice long prevalent in our system of commerce and taught in any introductory finance class.”) (citation omitted); Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Symantec Corp., 838 F.3d 1307, 1313, 120 USPQ2d 1353, 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“The category of abstract ideas embraces ‘fundamental economic practice[s] long prevalent in our system of commerce,’ … including ‘longstanding commercial practice[s]’”).

An example of a case identifying a claim as reciting a fundamental economic practice is Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 609, 95 USPQ2d 1001, 1009 (2010). The fundamental economic practice at issue was hedging or protecting against risk. The applicant in Bilski claimed “a series of steps instructing how to hedge risk,” i.e., how to protect against risk. 561 U.S. at 599, 95 USPQ2d at 1005. The method allowed energy suppliers and consumers to minimize the risks resulting from fluctuations in market demand for energy. The Supreme Court determined that hedging is “fundamental economic practice” and therefore is an “unpatentable abstract idea.” 561 U.S. at 611-12, 95 USPQ2d at 1010.

Another example of a case identifying a claim as reciting a fundamental economic practice is Bancorp Services., L.L.C. v. Sun Life Assurance Co. of Canada (U.S.), 687 F.3d 1266, 103 USPQ2d 1425 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The fundamental economic practice at issue in Bancorp pertained to insurance. The patentee in Bancorp claimed methods and systems for managing a life insurance policy on behalf of a policy holder, which comprised steps including generating a life insurance policy including a stable value protected investment with an initial value based on a value of underlying securities, calculating surrender value protected investment credits for the life insurance policy; determining an investment value and a value of the underlying securities for the current day; and calculating a policy value and a policy unit value for the current day. 687 F.3d at 1270-71, 103 USPQ2d at 1427. The court described the claims as an “attempt to patent the use of the abstract idea of [managing a stable value protected life insurance policy] and then instruct the use of well-known [calculations] to help establish some of the inputs into the equation.” 687 F.3d at 1278, 103 USPQ2d at 1433 (alterations in original) (citing Bilski).

Other examples of "fundamental economic principles or practices" include:

“Commercial interactions” or “legal interactions” include agreements in the form of contracts, legal obligations, advertising, marketing or sales activities or behaviors, and business relations.

An example of a claim reciting a commercial or legal interaction, where the interaction is an agreement in the form of contracts, is found in buySAFE, Inc. v. Google, Inc., 765 F.3d. 1350, 112 USPQ2d 1093 (Fed. Cir. 2014). The agreement at issue in buySAFE was a transaction performance guaranty, which is a contractual relationship. 765 F.3d at 1355, 112 USPQ2d at 1096. The patentee claimed a method in which a computer operated by the provider of a safe transaction service receives a request for a performance guarantee for an online commercial transaction, the computer processes the request by underwriting the requesting party in order to provide the transaction guarantee service, and the computer offers, via a computer network, a transaction guaranty that binds to the transaction upon the closing of the transaction. 765 F.3d at 1351-52, 112 USPQ2d at 1094. The Federal Circuit described the claims as directed to an abstract idea because they were “squarely about creating a contractual relationship--a ‘transaction performance guaranty’.” 765 F.3d at 1355, 112 USPQ2d at 1096.

Other examples of subject matter where the commercial or legal interaction is an agreement in the form of contracts include:

An example of a claim reciting a commercial or legal interaction in the form of a legal obligation is found in Fort Properties, Inc. v. American Master Lease, LLC, 671 F.3d 1317, 101 USPQ2d 1785 (Fed Cir. 2012). The patentee claimed a method of “aggregating real property into a real estate portfolio, dividing the interests in the portfolio into a number of deedshares, and subjecting those shares to a master agreement.” 671 F.3d at 1322, 101 USPQ2d at 1788. The legal obligation at issue was the tax-free exchanges of real estate. The Federal Circuit concluded that the real estate investment tool designed to enable tax-free exchanges was an abstract concept. 671 F.3d at 1323, 101 USPQ2d at 1789.

Other examples of subject matter where the commercial or legal interaction is a legal obligation include:

An example of a claim reciting advertising is found in Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, 772 F.3d 709, 714-15, 112 USPQ2d 1750, 1753-54 (Fed. Cir. 2014). The patentee in Ultramercial claimed an eleven-step method for displaying an advertisement (ad) in exchange for access to copyrighted media, comprising steps of receiving copyrighted media, selecting an ad, offering the media in exchange for watching the selected ad, displaying the ad, allowing the consumer access to the media, and receiving payment from the sponsor of the ad. 772 F.3d. at 715, 112 USPQ2d at 1754. The Federal Circuit determined that the "combination of steps recites an abstraction—an idea, having no particular concrete or tangible form" and thus was directed to an abstract idea, which the court described as "using advertising as an exchange or currency." Id.

Other examples of subject matter where the commercial or legal interaction is advertising, marketing or sales activities or behaviors include:

An example of a claim reciting business relations is found in Credit Acceptance Corp. v. Westlake Services, 859 F.3d 1044, 123 USPQ2d 1100 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The business relation at issue in Credit Acceptance is the relationship between a customer and dealer when processing a credit application to purchase a vehicle. The patentee claimed a “system for maintaining a database of information about the items in a dealer’s inventory, obtaining financial information about a customer from a user, combining these two sources of information to create a financing package for each of the inventoried items, and presenting the financing packages to the user.” 859 F.3d at 1054, 123 USPQ2d at 1108. The Federal Circuit described the claims as directed to the abstract idea of “processing an application for financing a loan” and found “no meaningful distinction between this type of financial industry practice” and the concept of intermediated settlement in Alice or the hedging concept in Bilski. 859 F.3d at 1054, 123 USPQ2d at 1108.

Another example of subject matter where the commercial or legal interaction is business relations includes:

The sub-grouping “managing personal behavior or relationships or interactions between people” include social activities, teaching, and following rules or instructions.

An example of a claim reciting managing personal behavior is Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Capital One Bank (USA), 792 F.3d 1363, 115 USPQ2d 1636 (Fed. Cir. 2015). The patentee in this case claimed methods comprising storing user-selected pre-set limits on spending in a database, and when one of the limits is reached, communicating a notification to the user via a device. 792 F.3d. at 1367, 115 USPQ2d at 1639-40. The Federal Circuit determined that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “tracking financial transactions to determine whether they exceed a pre-set spending limit (i.e., budgeting)”, which “is not meaningfully different from the ideas found to be abstract in other cases before the Supreme Court and our court involving methods of organizing human activity.” 792 F.3d. at 1367-68, 115 USPQ2d at 1640.

Other examples of managing personal behavior recited in a claim include:

An example of a claim reciting social activities is Voter Verified, Inc. v. Election Systems & Software, LLC, 887 F.3d 1376, 126 USPQ2d 1498 (Fed. Cir. 2018). The social activity at issue in Voter Verified was voting. The patentee claimed “[a] method for voting providing for self-verification of a ballot comprising the steps of” presenting an election ballot for voting, accepting input of the votes, storing the votes, printing out the votes, comparing the printed votes to votes stored in the computer, and determining whether the printed ballot is acceptable. 887 F.3d at 1384-85, 126 USPQ2d at 1503-04. The Federal Circuit found that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “voting, verifying the vote, and submitting the vote for tabulation”, which is a “fundamental activity that forms the basis of our democracy” and has been performed by humans for hundreds of years. 887 F.3d at 1385-86, 126 USPQ2d at 1504-05.

Another example of a claim reciting social activities is Interval Licensing LLC, v. AOL, Inc., 896 F.3d 1335, 127 USPQ2d 1553 (Fed. Cir. 2018). The social activity at issue was the social activity of “’providing information to a person without interfering with the person’s primary activity.’” 896 F.3d at 1344, 127 USPQ2d 1553 (citing Interval Licensing LLC v. AOL, Inc., 193 F. Supp.3d 1184, 1188 (W.D. 2014)). The patentee claimed an attention manager for acquiring content from an information source, controlling the timing of the display of acquired content, displaying the content, and acquiring an updated version of the previously-acquired content when the information source updates its content. 896 F.3d at 1339-40, 127 USPQ2d at 1555. The Federal Circuit concluded that “[s]tanding alone, the act of providing someone an additional set of information without disrupting the ongoing provision of an initial set of information is an abstract idea,” observing that the district court “pointed to the nontechnical human activity of passing a note to a person who is in the middle of a meeting or conversation as further illustrating the basic, longstanding practice that is the focus of the [patent ineligible] claimed invention.” 896 F.3d at 1344-45, 127 USPQ2d at 1559.

An example of a claim reciting following rules or instructions is In re Marco Guldenaar Holding B.V., 911 F.3d 1157, 1161, 129 USPQ2d 1008, 1011 (Fed. Cir. 2018). The patentee claimed a method of playing a dice game including placing wagers on whether certain die faces will appear face up. 911 F.3d at 1160; 129 USPQ2d at 1011. The Federal Circuit determined that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “rules for playing games”, which the court characterized as a certain method of organizing human activity. 911 F.3d at 1160-61; 129 USPQ2d at 1011.

Other examples of following rules or instructions recited in a claim include:

The courts consider a mental process (thinking) that “can be performed in the human mind, or by a human using a pen and paper” to be an abstract idea. CyberSource Corp. v. Retail Decisions, Inc., 654 F.3d 1366, 1372, 99 USPQ2d 1690, 1695 (Fed. Cir. 2011). As the Federal Circuit explained, “methods which can be performed mentally, or which are the equivalent of human mental work, are unpatentable abstract ideas the ‘basic tools of scientific and technological work’ that are open to all.’” 654 F.3d at 1371, 99 USPQ2d at 1694 (citing Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 175 USPQ 673 (1972)). See also Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs. Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 71, 101 USPQ2d 1961, 1965 (2012) (“‘[M]ental processes[] and abstract intellectual concepts are not patentable, as they are the basic tools of scientific and technological work’” (quoting Benson, 409 U.S. at 67, 175 USPQ at 675)); Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 589, 198 USPQ 193, 197 (1978) (same).

Accordingly, the “mental processes” abstract idea grouping is defined as concepts performed in the human mind, and examples of mental processes include observations, evaluations, judgments, and opinions. A discussion of concepts performed in the human mind, as well as concepts that cannot practically be performed in the human mind and thus are not “mental processes”, is provided below with respect to point A.

The courts do not distinguish between mental processes that are performed entirely in the human mind and mental processes that require a human to use a physical aid (e.g., pen and paper or a slide rule) to perform the claim limitation. See, e.g., Benson, 409 U.S. at 67, 65, 175 USPQ at 674-75, 674 (noting that the claimed “conversion of [binary-coded decimal] numerals to pure binary numerals can be done mentally,” i.e., “as a person would do it by head and hand.”); Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1139, 120 USPQ2d 1473, 1474 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (holding that claims to a mental process of “translating a functional description of a logic circuit into a hardware component description of the logic circuit” are directed to an abstract idea, because the claims “read on an individual performing the claimed steps mentally or with pencil and paper”). Mental processes performed by humans with the assistance of physical aids such as pens or paper are explained further below with respect to point B.

Nor do the courts distinguish between claims that recite mental processes performed by humans and claims that recite mental processes performed on a computer. As the Federal Circuit has explained, “[c]ourts have examined claims that required the use of a computer and still found that the underlying, patent-ineligible invention could be performed via pen and paper or in a person’s mind.” Versata Dev. Group v. SAP Am., Inc., 793 F.3d 1306, 1335, 115 USPQ2d 1681, 1702 (Fed. Cir. 2015). See also Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Symantec Corp., 838 F.3d 1307, 1318, 120 USPQ2d 1353, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (‘‘[W]ith the exception of generic computer-implemented steps, there is nothing in the claims themselves that foreclose them from being performed by a human, mentally or with pen and paper.’’); Mortgage Grader, Inc. v. First Choice Loan Servs. Inc., 811 F.3d 1314, 1324, 117 USPQ2d 1693, 1699 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (holding that computer-implemented method for "anonymous loan shopping" was an abstract idea because it could be "performed by humans without a computer"). Mental processes recited in claims that require computers are explained further below with respect to point C.

Because both product and process claims may recite a “mental process”, the phrase “mental processes” should be understood as referring to the type of abstract idea, and not to the statutory category of the claim. The courts have identified numerous product claims as reciting mental process-type abstract ideas, for instance the product claims to computer systems and computer-readable media in Versata Dev. Group. v. SAP Am., Inc., 793 F.3d 1306, 115 USPQ2d 1681 (Fed. Cir. 2015). This concept is explained further below with respect to point D.

The following discussion is meant to guide examiners and provide more information on how to determine whether a claim recites a mental process. Examiners should keep in mind the following points A, B, C, and D when performing this evaluation.

A. A Claim With Limitation(s) That Cannot Practically be Performed in the Human Mind Does Not Recite a Mental Process

Claims do not recite a mental process when they do not contain limitations that can practically be performed in the human mind, for instance when the human mind is not equipped to perform the claim limitations. See SRI Int’l, Inc. v. Cisco Systems, Inc., 930 F.3d 1295, 1304 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (declining to identify the claimed collection and analysis of network data as abstract because “the human mind is not equipped to detect suspicious activity by using network monitors and analyzing network packets as recited by the claims”); CyberSource, 654 F.3d at 1376, 99 USPQ2d at 1699 (distinguishing Research Corp. Techs. v. Microsoft Corp., 627 F.3d 859, 97 USPQ2d 1274 (Fed. Cir. 2010), and SiRF Tech., Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 601 F.3d 1319, 94 USPQ2d 1607 (Fed. Cir. 2010), as directed to inventions that ‘‘could not, as a practical matter, be performed entirely in a human’s mind’’).

Examples of claims that do not recite mental processes because they cannot be practically performed in the human mind include:

In contrast, claims do recite a mental process when they contain limitations that can practically be performed in the human mind, including for example, observations, evaluations, judgments, and opinions. Examples of claims that recite mental processes include: